Is the United States likely to collapse? Should social justice advocates respond?

Key points

- In this article, I explore my concerns about whether the United States could realistically witness a political collapse in the next couple of decades.

- I’m motivated by the need to figure out whether social justice advocates working in the United States (e.g. animal advocates, or people working on whatever specific social issue) should give serious thought to incorporating the risk of collapse into their advocacy strategies. This could involve conducting advocacy in other countries or switching to working directly on reforming the political system.

- My conclusion is that the United States does seem to be at a high risk of collapsing, and that there are no signs of this risk going away any time soon. Social advocates might be wise to consider .

This article was inspired by J.T. Stanley’s article: “The top X-factor EA neglects: destabilization of the United States”. I’d encourage you to read that article before my article, though my article is standalone and can be read by itself. Overall, I began in a position of disagreement with many of Stanley’s claims, but after examining some evidence I found myself updating towards agreeing with Stanley’s view on pretty much everything. My article, while based on data and academic research, is neither systematic nor authoritative.

1. Introduction

1.1 Motivating question

The purpose of this article is to explore the following question:

Is the United States at such a high probability of “collapsing” in the near-term future (e.g. 0 - 20 years) that people working on social advocacy within the United States ought to switch their strategies?

My motivating question can be divided into three parts:

- Has something fundamental changed that makes the United States at the current point in time (year 2024) unprecedented when compared to previous points in time (e.g. the 1960s civil rights protests and associated unrest; Al Gore’s challenge of the 2000 election; etc)?

- Could that something plausibly cause the United States to collapse?

- Is that risk sufficiently high to warrant a change in the strategy of advocates of various social causes?

For example, if the United States is likely to collapse, would the wins of any particular social movement today be erased with one order from a charismatic dictator (or even by the democratic votes of legislatures in multiple, independent successor states)? Should environmental advocates forget about the environment and instead work on reforming the American political system? Should animal advocates stop working on obtaining cage-free commitments in the United States and instead, say, work on commitments in Canada? Should people working on advancing the rights of queer Americans, Black Americans, and/or women (and the people working on limiting those rights) forget about their current projects on the grounds that a victory won today might be submerged under the tidal wave of political collapse tomorrow?

The collapse of the United States, like any other major geopolitical event, is hard or impossible to predict accurately. However, we can examine the conditions that make such an event more likely or less likely. In other words, while we cannot predict if (or when) somebody is going to light a match, we look around to see if the floor is covered in tinder.

I do not address how people could go about fixing any potential issue. Obviously, that is a question of the highest importance, but it’s not one that I’m exploring in this article. Likewise, this article isn’t systematic or authoritative by any means, and I haven’t given this article the same level of systematic attention to detail that I maintain during my normal, day-to-day research on animal welfare (not that a systematic analysis of “all political thought” would somehow produce a consensus answer). It seems like everyone in the world has their own take on the political situation in the United States. My approach here is to begin with a few background assumptions, look at some data and complement that data with academic analyses that account for those background assumptions, and then come to a personal conclusion about my motivating question.

1.2 Background assumptions

Like any researcher, I bring my own assumptions and institutions into this article. The most important of these are as follows:

-

When a country undergoes a political collapse, we cannot expect policies that were won in the period immediately before that collapse to survive the collapse (Note 1). For example, if the United States collapses into multiple, independent successor states, we can’t expect a cage-free commitment made by a retailer to be honoured. Likewise, if a dictator comes to power, I wouldn’t expect that dictator to respect the existing bodies of federal and state legislation. This means that social advocacy today (for whatever cause) is not necessarily effective or tractable if the system in which that advocacy is conducted could collapse.

- Countries collapse all the time. Democracies die. Evil regimes do come to power. There is nothing inherently special about any particular point in history, including our own.

- That said, the United States has withstood many periods of intense, violent civil conflict without collapsing (1). At least until the 2021 Capitol attack, I felt that the polarisation and violence in the 21st century is nowhere near as bad as in the years immediately before the Civil War (2). As expressed in the blurb of Freeman’s book Field of Blood, there was “physical violence on the floor of the U.S. Congress in the decades before the Civil War. Legislative sessions were often punctuated by mortal threats, canings, flipped desks, and all-out slugfests. When debate broke down, congressmen drew pistols and waved Bowie knives. One representative even killed another in a duel. Many were beaten and bullied in an attempt to intimidate them into compliance, particularly on the issue of slavery.”

- I do not define “collapse”. I’m using that term to mean something resembling the French Revolution (and the subsequent collapses after that revolution); or the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Nazi Germany; or the secession of the Confederacy, had that secession been successful; or the Chinese Civil War. The defining characteristic is the sweeping changes to most or all areas of policy (and therefore agricultural production), rather than whether the subsequent regime is morally good or bad or whatever. There are more tame and controlled political transformations that I would not consider a “collapse”, which would include, for example, the Velvet Divorce of Czechoslovakia; or Brexit; or perhaps the transition between the Fourth and Fifth French Republics.

- The functions and operations of the United States government have undergone profound transformations even since the Civil War. Most notably, this occurred in response to the Great Depression and then in response to the civil rights protests in the 1960s and the associated conservative reaction (1,3). The details of these transformations are explored in greater detail below, but this is an assumption I held before going into this research.

-

A feature of the United States federal political system that strikes me as odd (at least among countries of the Global North) is the existence of both a) a two-party system, and b) weak party whips (Note 2). The United Kingdom and Australia both have two-party systems and strong party whips, while countries in Western Europe tend to have multi-party systems. It’s not immediately obvious how this feature plays into the risk of political collapse, but I think it is worth understanding that the political system of the United States is actually pretty unusual from a global perspective (and the book by Jacobs and Milkis does provide one perspective on the strength of the parties in a two-party system, see below). I feel similarly about, but am less educated on, the Electoral College.

- The United States is the world’s biggest superpower (in military and economic terms) but that role has been gradually diminishing, at least over the past few decades (8). A political collapse of the United States would have immense consequences for the safety of people in many other countries (beginning with my own country, Australia).

- On a personal level, I’m frightened by the present inability of Congress to function normally by passing bills (Note 3). (See section 3.3 of this article.)

2. Readings of academic books

I found two academic books particularly illuminating:

- What Happened to the Vital Center? Presidentialism, Populist Revolt, and the Fracturing of America One by Nicholas Jacobs and Sidney Milkis (2022). This book provides an explanation for the divisiveness, partisanship, and violence in contemporary American politics by tracing the history of how key federal institutions emerged over the past century or so (e.g. a powerful executive) and how, paradoxically, partisanship has increased even as the major parties themselves have lost the ability to filter populist tendencies. I think this book is a fantastic example of what academic research can be - the writing is engaging, its explanations are placed in a long historical trajectory, and the authors are humble about their position and acknowledge the diversity of views on this topic held by academics.

- Radical American Partisanship: Mapping Violent Hostility, Its Causes, and the Consequences for Democracy by Nathan P. Kalmoe and Lilliana Mason (2022). This book provides lots of original survey data on partisanship, polarization, and political violence from over the past decade or so. The book’s data is extremely detailed, and the only criticism I have of this book is the occasional tendency to unfairly blame the Republican party in particular (which Jacobs and Milkis avoid doing).

I’ll now describe the argument of each of these two books, and implications for the future of the United States, in detail.

2.1 What Happened to the Vital Center? by Jacobs and Milkis

In essence, Jacobs and Milkis argue that it is not new for politicians to make populist appeals, but that politicians who make such appeals are no longer filtered by mediating institutions - specifically, powerful party establishments. The stakes of political contests have also become higher due to the rise of the executive branch.

The core argument of this book is as follows:

- Firstly, the authors define populism as “unmediated democratic politics.” Basically, they’re talking about politicians advocating on behalf of “the people”, tearing down the elite establishments, etc. As the authors write, populism is not necessarily a bad thing, but unchecked populism can be: “Populism thrives in a democracy, and any institutional regime that can lay claim to eradicating populism would likely fail to meet the standards of self-rule and contested elections. Populism is also an ideologically contingent phenomenon - at times it is reactionary, other times progressive. Historians’ interpretations of various populist movements change: a reflection of their own time and understanding what constitutes social justice. […] Although populism often goes hand in hand with, or exploits, repulsive xenophobic and racist beliefs, populism’s defining feature is a distrust of public officials.”

-

Historically, the Republican and Democratic parties have both acted as gatekeepers, filtering ambitious actors and populist tendencies (Note 4). However, the power of both the Republican and Democratic parties, as gatekeeping organizations, has weakened due to specific reforms by activists that “culminated with the McGovern-Fraser reforms, which established a system of open caucuses and direct primaries by the early 1970s.” The Democratic party was the first to succumb to this activism and undergo these populist reforms, though the Republican party followed soon after.

- The executive power of the president has expanded since the 1930s. Specifically, the Executive Office of the President (which comprises the White House Office, the Office of Management and Budget, and other staff agencies) was created as part of the New Deal and the 1939 Executive Reorganization Act.

- There has been a rise in “movement politics” - that is, politics with social or moral aims - since the 1960s.

- Thus, the stakes of party politics have become higher; the moral shadow over contests for the presidency has become longer; and the incentive of presidents to manage disagreements has decreased.

- Thus, while parties as organizations have become weaker, partisanship itself - the identification of people and politicians with one political party and disengagement with the rival party - has paradoxically become stronger.

- We have thus arrived at “executive-centered partisanship”. In the words of the authors: “American politics is now shaped by weak parties and passionate, angry partisanship. Parties were, at one-point, central mediating institutions. Consequently, they played a critical role in maintaining a healthy civic culture during previous periods of populist unrest. Populism is not new, but the hollowed out, institutionally aligned party system that once contained it is.”

- As such, the political situation in the United States has become particularly unstable, even when compared to previous points in history: “contemporary partisanship is especially combustible because it takes place in the absence of vital party organizations that historically have channeled democratic unrest and popular disagreement into more structured and less militant forms of political engagement.”

- The authors suggest that this political reality “poses an existential threat to liberal democracy.”

The book also offers an analysis of where the American political system might go from here. In short, the trends that the authors have identified show no sign of abating.

- The events of 2020 onwards are unprecedented in at least some ways: “Although harsh party conflict in the United States is not new, the momentous and polarizing events of 2020 were mired in an all-consuming partisanship that the country had not witnessed since the Civil War.”

- While Obama and Biden may not have attempted to foment insurrection in the same way that Trump did, those two Democratic presidents have certainly operated within (and even taken advantage of) this new reality of executive-centered partisanship.

- Moreover, Biden’s presidency has shown how the problems are persisting, not improving: “Biden launched his presidency with a dramatic display of executive-centered partisanship. […] During his first 100 days in office, Biden signed more executive actions than any other president since Franklin Roosevelt.”

- The results and aftermath of the 2020 election have not been a rejection of Trump himself. The 2020 election was extremely close. Since the 2021 Capitol attack, the Republican Party has continued to support Trump: “[…] Trump’s spell over the Republican Party persisted. […] 139 House Republicans and eight Republican senators still voted against certifying some of the Electoral College votes. With unwavering loyalty to Trump - and a lot of posturing for the next presidential nomination - they persisted in their assault on the ramparts of democracy […]”

2.2 Radical American Partisanship by Kalmoe and Mason

Kalmoe and Mason present detailed survey data of the American public on partisanship and political violence. The data is extremely nuanced and well-informed by both history and psychology.

Some key findings are as follows:

- There is basically no long-term data on support for political violence in the United States. However, when past surveys have asked about support for political violence, the authors have deliberately posed the same questions today using similar sampling methods. (I think this approach to obtaining data is truly admirable.) In the 1970s, 1990s, and 2010s, very few people expressed support for political violence. When the authors replicated those surveys in 2020, they found that the number of people expressing support for political violence was similarly very low. The only change is that when the overwhelming majority of people in previous surveys rejected political violence, respondents in 2020 were more likely to respond that they “don’t know”. The authors, wisely, advise caution when interpreting that observation.

- Support for political violence is a risk factor, but it does not cause political violence in itself. The authors quote a 2019 report that warned “we have the tinder for political violence”. Signals from political elites can provide the spark that is needed for violence to actually erupt. One such signal was the rhetoric used by Trump in refusing to concede the 2020 election and advocating for violence.

- The people who participated in the 2021 Capitol attack differed from the usual profile of people who commit political violence: “The political scientist Robert Pape […] found that most [participants in the Capitol attack] were middle-class, middle-aged white men who had no known ties to right-wing extremist groups already linked to violence. Only about one in ten had militia ties, though an NPR report found that 14 percent were current or former members of the US military or law enforcement. In other words, most resembled ordinary Trump supporters, which Pape interprets as a dangerous sign for the future - a normalization of radicalism. Those profiles contrast with those arrested for right-wing violence in the past, nearly half of whom were affiliated with supremacist gangs or far-right militias. Likewise, only 9 percent of January 6 arrestees were unemployed and two-thirds were over thirty-five, in contrast with past attackers, one-quarter of whom were unemployed with over 60 percent under thirty years old. Forty percent [of the Capitol arrestees] held white-collar jobs.”

- People’s support for political violence depends very strongly on the context. Even when survey participants reject political violence in general, those same participants may also express support for particular, historical acts of political violence (e.g. American Revolution) or for political violence in hypothetical, future scenarios (e.g. the government is corrupt and imprisoning its critics). Most people depend on cues from political leaders and their communities.

- Losing an election can radicalize partisans even further, especially when the loss is framed by political elites in apocalyptic terms - which is how Trump framed his loss of the 2020 election immediately before the 2021 Capitol attack.

- Finally, the authors express one point as a side note, but I think it is actually extremely relevant: “[…] the ‘Stop the Steal’ slogan used by Trump supporters in 2020 had been coined by Trump ally Roger Stone’s political action committee in 2016 - in anticipation of a Trump loss that never occurred.” This supports the perspective offered by Jacobs and Milkis’s What Happened to the Vital Center? - the groundwork for America’s contemporary political crises has existed for a long time.

3. Graphs

I obtained data on some key metrics and graphed them below. I chose metrics that seem to capture important dynamics in the frameworks proposed by Stanley’s article, Jacobs and Milkis’s book, and Kalmoe and Mason’s book. Not all variables in those frameworks have been (or can be) measured using data like this, so these graphs are obviously not a complete picture.

The following graphs all visualize the period of time between 1945 and the present day. In most cases, we don’t have data from before ~1990. Nevertheless, I’ve kept the graphs to show the same time period (1945 to today) for two reasons: firstly, this lets you easily compare different variables just by looking at the graphs; and secondly, this emphasizes the fact that we just don’t have a lot of data to inform our views on some of these political trends.

3.1 Feelings of the public towards political parties

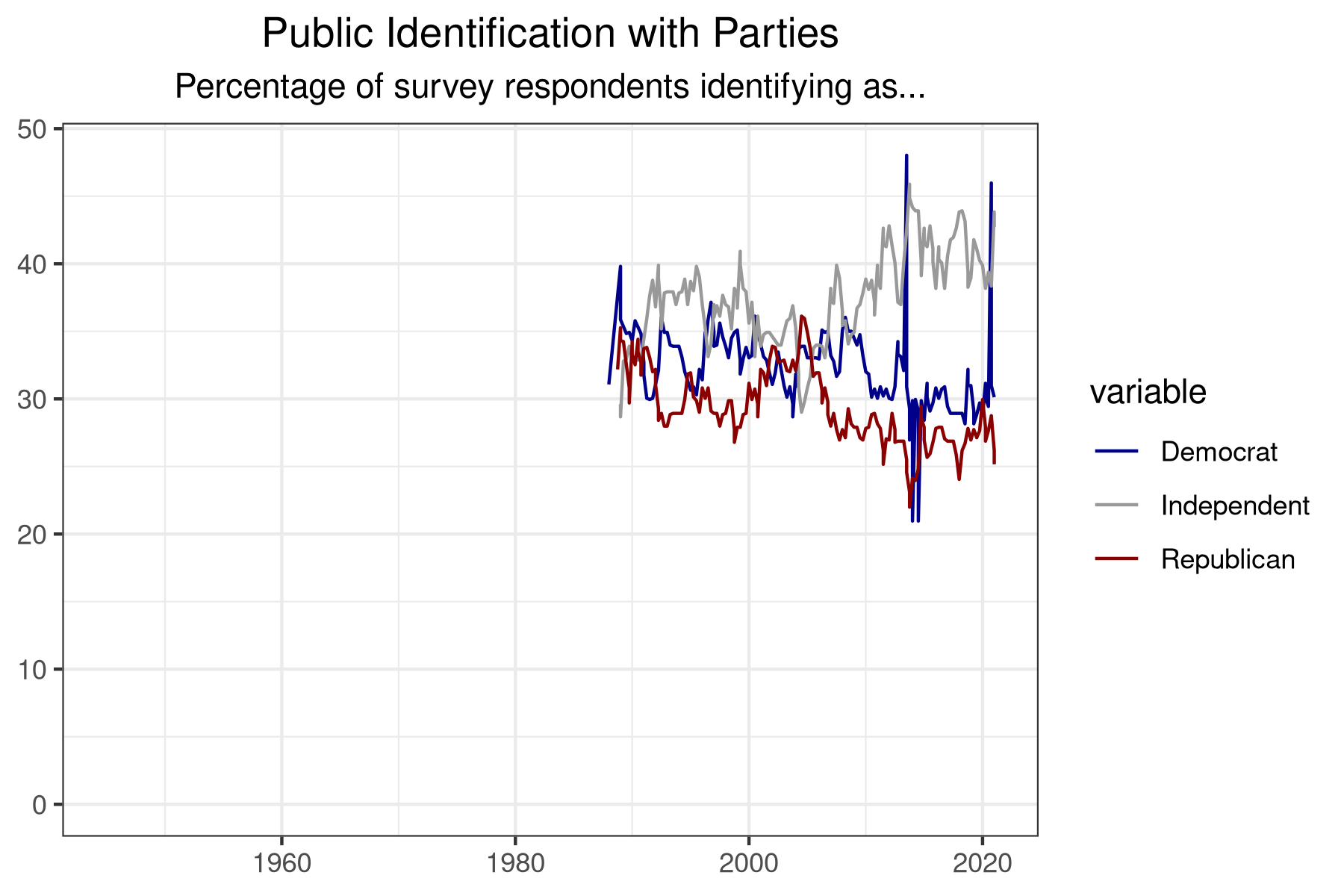

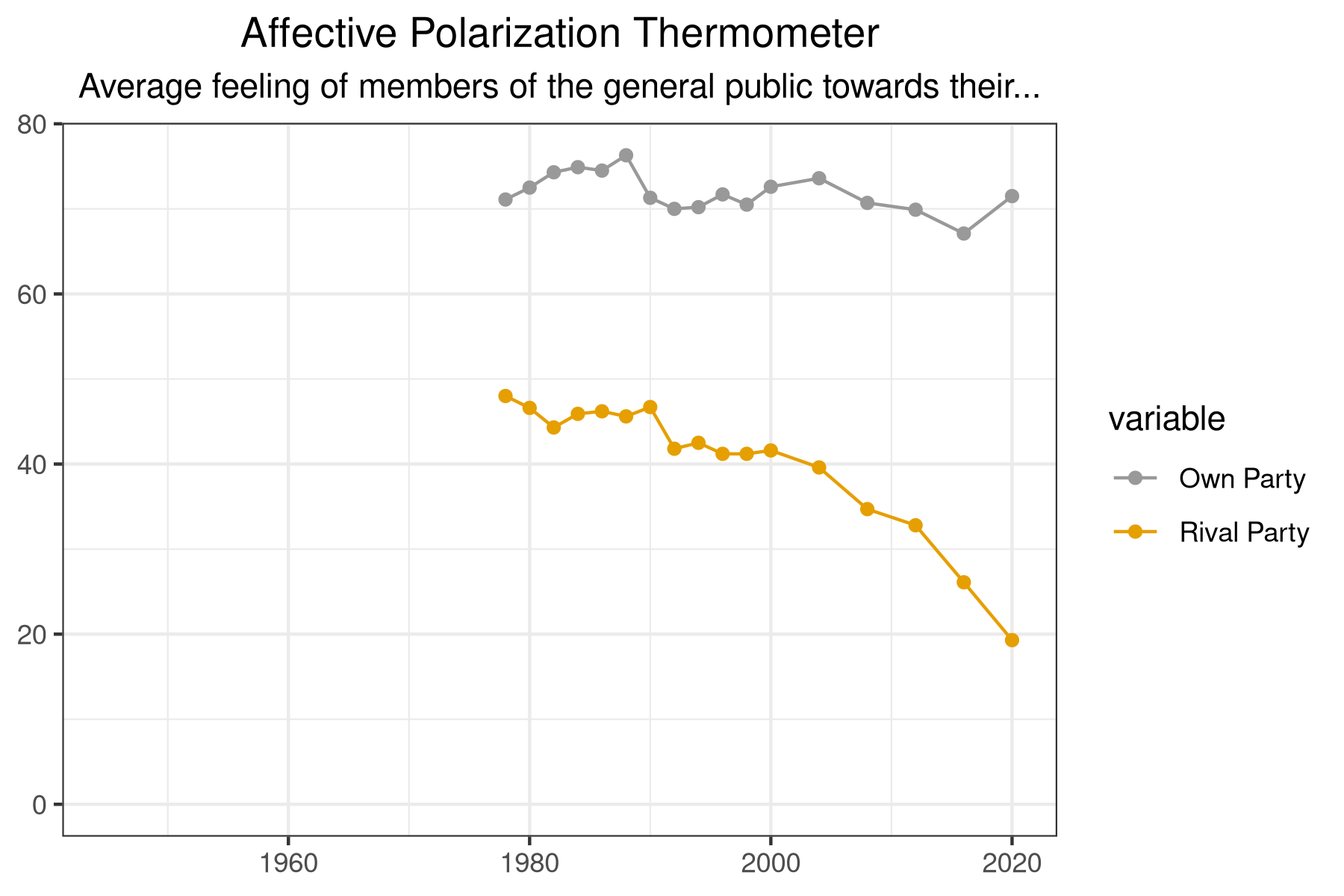

The percentage of the public identifying as Democrat or Republican hasn’t undergone any obvious changes, with the possible exception of a decline in both parties since ~2010. The percentage of people identifying as “independent” appears to have increased.

I don’t know how the increase of people identifying as “independent” is related to the “rise in partisanship” as identified by Jacobs and Milkis.

The feeling of people towards their own party has remained relatively constant. The feeling of people towards their rival party has declined. This seems consistent with a rise in partisanship as expressed by Jacobs and Milkis.

Data on party identification from Gallup. Data on affective polarization from American National Election Studies.

3.2 Partisan polarisation within Congress

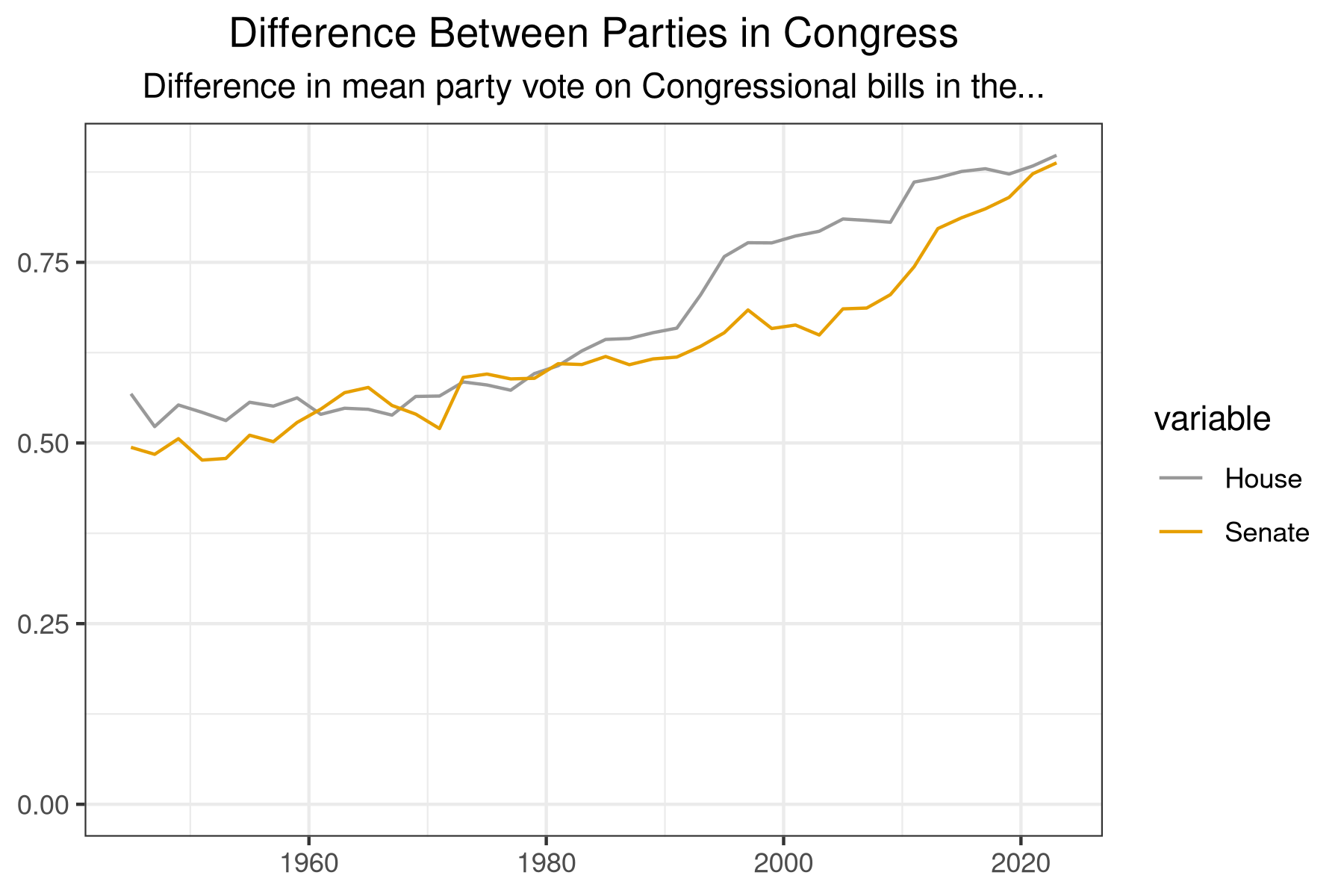

Within Congress, parties have become more polarized in how they vote on bills. That is, Democrat representatives have become more different from Republican representatives in their voting patterns (and vice-versa).

Data from Voteview.

3.3 Function of Congress

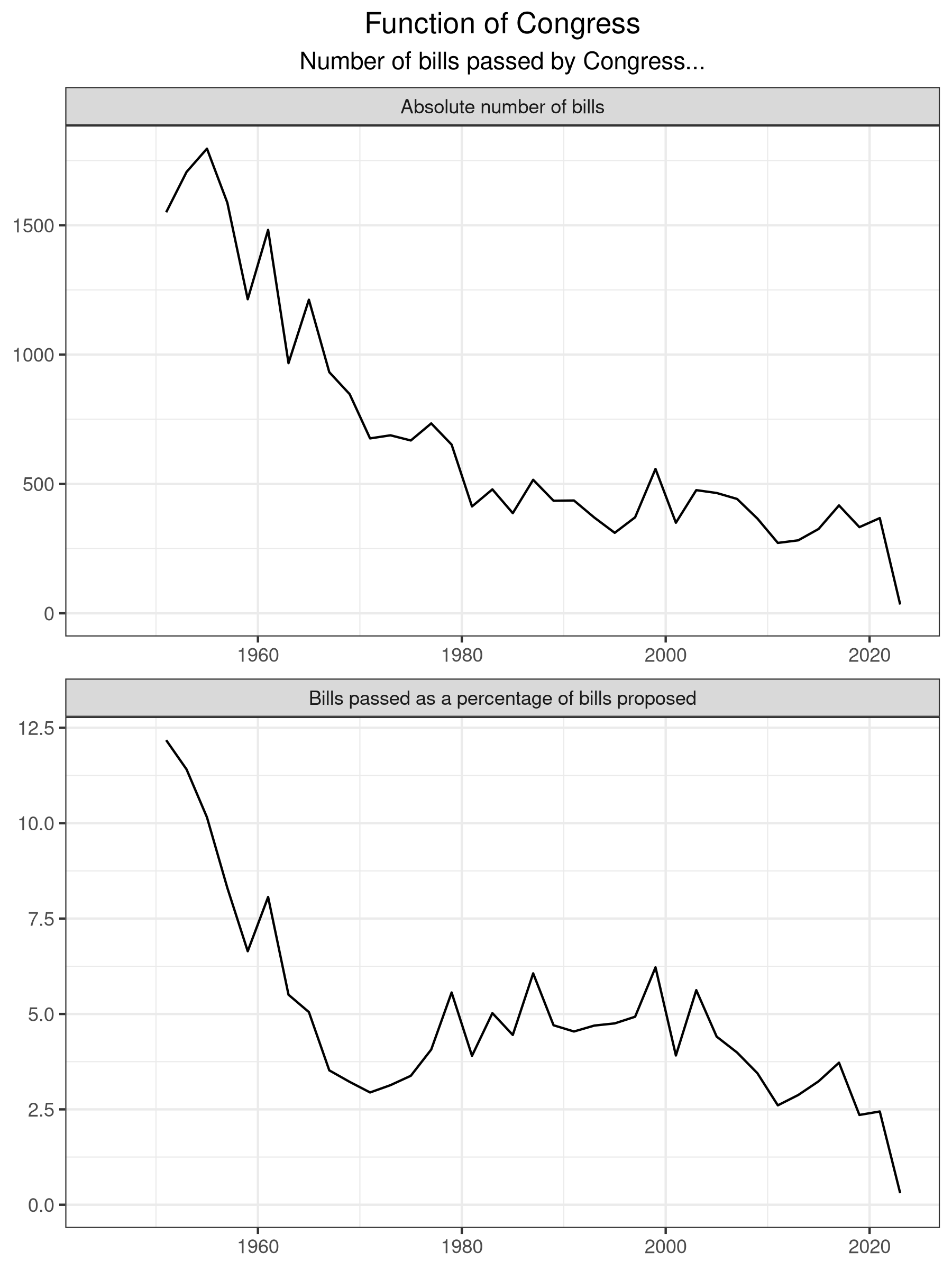

Since the 1950s, Congress has seen a remarkable decline in the number of bills passed during each session. We know that this isn’t because representatives are proposing fewer bills, as the decreasing trend holds even when we divide the number of bills passed by the number of bills proposed. By either metric, Congress is passing fewer bills than since the 1950s. (Data exists before this, but I haven’t obtained it.)

To me, this suggests that Congress is becoming worryingly ineffective. I don’t know whether this trend is caused solely by the filibuster in the Senate or whether other dynamics are involved too.

Data on bills from Congress.gov and Canen et al (4).

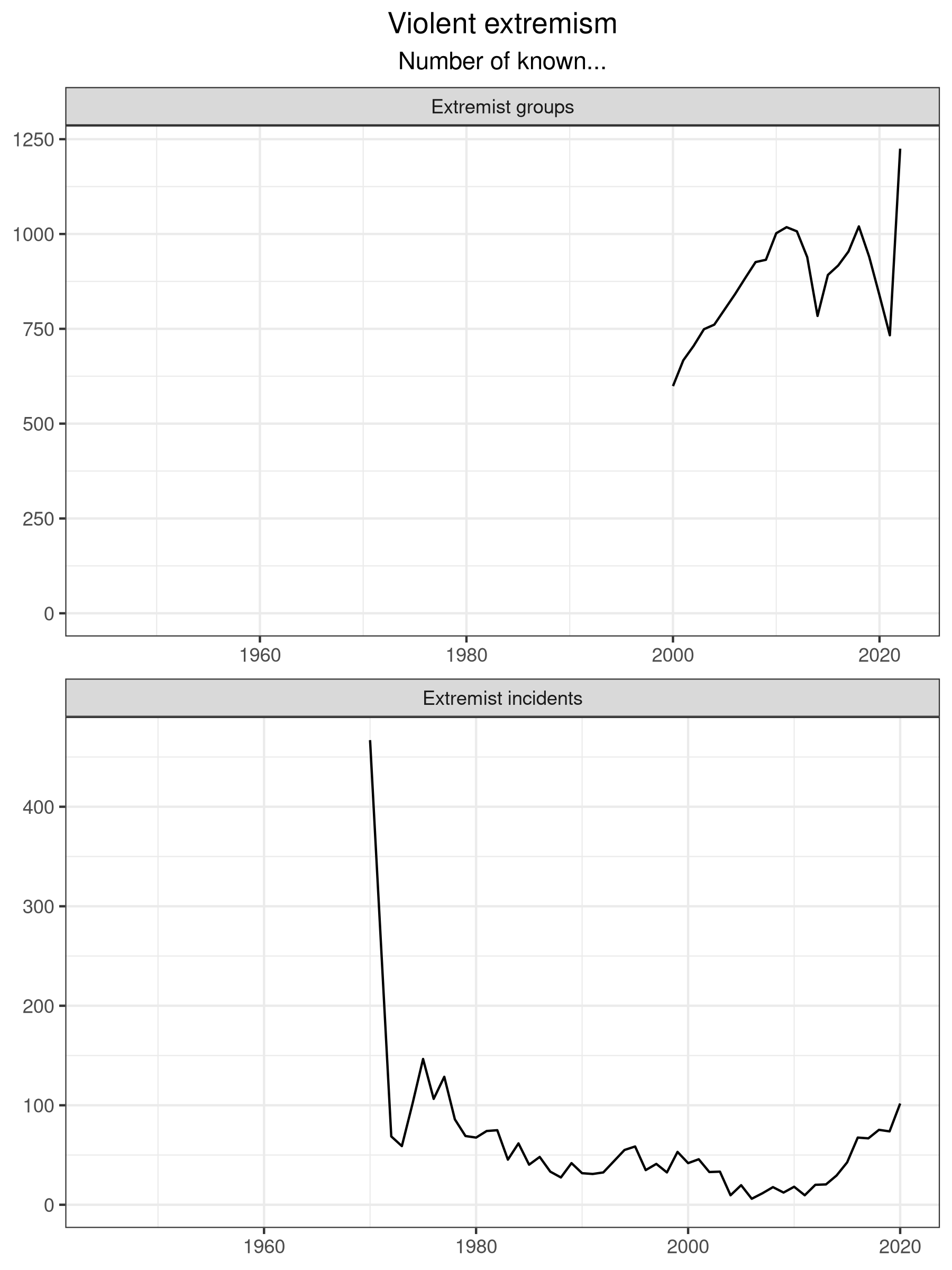

3.4 Extremist violence

The number of known extremist groups might be increasing over time, but the trend fluctuates - it’s hard to say for sure. The number of extremist incidents is increasing over time and is the highest that the United States has seen since the mid-1970s.

Data on the number of extremist groups from Southern Poverty Law Center. Data on the number of extremist incidents from Global Terrorism Database.

4. Other important but miscellaneous observations

4.1 Trump himself is not going away just yet

Jacobs and Milkis, in the later chapters of their book, make a compelling case that the Republican Party has doubled down on its support for Trump.

At the time of writing (February 2024), Metaculus has the following community forecasts:

- Trump is at 97% to win the Republican nomination.

- Trump is at 50% to be elected US President in 2024, compared to 46% for Biden (and 1.3% for Harris).

- Tellingly, the question “Will the next US presidential election also be considered fraudulent by the losing party?” is at 50% for yes.

4.2 Public support for political violence

In the academic literature, there is disagreement about how much credence we should put in surveys of the public’s support for political violence. Overall, I think this warrants a small update away from “a collapse is probable”.

The academic disagreement is as follows:

- In Westwood et al’s recent article “Current research overstates American support for political violence” (9), the authors argue that “self-reported attitudes on political violence are biased upward because of respondent disengagement and survey questions that allow multiple interpretations of political violence. Addressing question wording and respondent disengagement, we find that the median of existing estimates of support for partisan violence is nearly 6 times larger than the median of our estimates (18.5% versus 2.9%).”

- Kalmoe and Mason (who also wrote one of the books that I discussed in section 2 of this article) published a reply (10). They retort: “The idea that inattentive respondents might inflate percentages is smart, and the truly inattentive should be discarded. However, measures must discern better to retain sincere responses, especially since close attention correlates with trait aggression—a strong predictor of violent political views. Aggressive respondents are more likely to miss insubstantial details of a vignette and to endorse violence. This does not automatically invalidate their stated attitudes.”

- One survey organisation, Bright Line Watch, revised their survey questions to address the criticisms of Westwood et al. After doing so, Bright Line Watch’s revised survey does indeed find that support for political violence is lower: “[…] The interaction between inattention and a single response scale inflates estimates of support for threats, harassment, and violence (a problem that may affect many online surveys in which we are especially interested in responses that deviate from one end of a response scale). In contrast, our best estimates of public support for political violence, threats, and harassment are substantially lower than past research found. When we exclude inattentive respondents, first ask attentive respondents a binary question, and provide them with a specific definition or example where appropriate, reported support is 9% for threats, 8% for harassment, 6% for non-violent felonies, 4% for violent felonies, 4% for violence if the other party wins the 2024 election, 4% for violence on January 6, and 5% for violence to restore Trump to the presidency. These figures are much lower than we estimated using the original scale in October 2020.”

I think the criticisms raised by Westwood et al are well-argued and logically convincing. These criticisms appear even more convincing when one considers how the estimated support for political violence decreased after Bright Line Watch modified their survey questions. However, I also think that the data presented in Kalmoe and Mason’s book (and which I describe in section 2 of this article) is very nuanced and detailed, and there are many worrying trends that cannot be explained solely by the criticisms raised by Westwood et al.

4.3 Previous power grabs

No US Presidents have attempted to overturn the results of an election to the extent that Trump did (11). Trump’s attempted power grab after the 2020 election is truly unprecedented in US politics.

There are some incidents that could offer some precedent, but these do not strike me as terribly informative.

One possible precedent comes from the 2000 election, when the defeated Al Gore challenged the results of the election in court. As Jacobs and Milkis write (11): “[…] After the Court in the appropriately named case of_ Bush v Gore_ ruled against him, Gore stepped aside, and conceded defeat. Donald Trump never did […] Trump became the first president to use the “bully pulpit” to sow distrust in a free and fair election and overturn the constitutional process for ensuring a peaceful transition of power. Other presidents had stoked the base, fueled discord, and benefited from creating deep societal divisions. But Trump will always have the dubious distinction of being the first president to actively court a movement to “fight like hell,” to win at all costs, even if it meant violence against the government.”

Some state governors have refused to leave office. None of these attempts were successful. Quoting from Wikipedia:

- Edmund J Davis, 1873: “When President Grant refused to send troops to the defeated governor’s rescue, Davis reluctantly left the capital in January 1874.”

- Wild Bill Langer, 1934: “It came to a head in July, 1934, when the state Supreme Court ruled that Langer needed to go and Olson assumed the role. […] Still, Langer refused to leave office. Crowds took to the street chanting ‘We want Langer,’ Robinson wrote. After the declaration of martial law, much rested on who Sarles recognized as governor and from whom he would take orders. Ultimately, Sarles went with Olson, and with the National Guard out of his corner, Langer finally gave up the governorship.”

- Georgia’s Three-Governors Controversy, 1946-7: “In March 1947 the Georgia Supreme Court ruled that Melvin E. Thompson was the rightful governor because he was lieutenant governor–elect when Eugene Talmadge died. In a five-to-two decision the justices ruled that Thompson would be the acting governor until a special election could be held to decide the remainder of the original term, which would have run from 1947 to 1951. Within two hours of the court decision, Herman Talmadge left the governor’s office.”

- Bull Connor, 1962: “On 23 May 1963, the Alabama Supreme Court ordered Connor and the other city commissioners to vacate their offices.”

I don’t think that these failed attempts by state governors are terribly informative about what the outcome might be should another 21st century President attempt to overturn the results of an election. I was surprised to learn that state governors have sometimes refused to leave office, but the incentives and power structures at the state level (and at those particular points in time) are so different to the power structures operating at the Federal level today.

4.4 Infiltration of law enforcement by extremists

The convert infiltration of law enforcement by extremists (mainly white supremacists) seems to be a genuine problem (12,13). I think this phenomenon warrants a small update in the direction of “a collapse is probable” for the reasons that J.T. Stanley explains. For obvious reasons, we have no data on the specific extent of this problem or how that extent has changed over time.

5. Conclusion

To give my current positions on the questions that I posed in the introduction to this article:

Q: Has something fundamental changed that makes the United States at the current point in time (year 2024) unprecedented when compared to previous points in time (e.g. the 1960s civil rights protests and associated unrest; Al Gore’s challenge of the 2000 election; etc)?

A: Yes.

The political system of the United States today is unprecedented due to the power of the presidency (established in 1936), the level of partisanship (beginning in the 1960s and continuing to the present day), and the absence of mediating institutions (as the gatekeeping role of the major parties was progressively weakened throughout the 20th century). These forces have been weakening the political system for decades.

Q: Could that something plausibly cause the United States to collapse?

A: Yes, this is very plausible.

The contemporary United States system is basically the same as it was when Obama won the presidency, and Obama didn’t try to foment an armed rebellion. Trump did. Next time, Trump might be more successful, especially as the underlying conditions only seem to have worsened since 2021 (with the Republican party doubling down on its support for Trump). Therefore, I think it’s fair to view the current political system as highly flammable tinder - it might not erupt into flames on its own, but it probably would only take one spark, which could come in the form of a Trump victory in 2024.

Q: Is that risk sufficiently high to warrant a change in the strategy of advocates of various social causes?

A: Possibly. I think so.

The community forecast currently has Trump at 50% to be elected President in 2024, and this view seems reasonable to me. Even if Trump loses in 2024, we may be in the exact same situation for the 2028 election, or we may see the rise of some equally populist and equally troubling demagogue from either party. Intuitively, it seems like the risk of the American political system collapsing is sufficiently high that it is worth reconsidering whether policy wins obtained by social advocates working within that system can be considered reliably influential and, therefore, effective.

short section on what we can do about it - i.e. how to action this information. some ideas that i haven’t thought about at all:

- working on stuff in other countries or international, e.g. canada, mexico, or whatever

- working on stuff that is “a physical thing in the world” and therefore plausibly more resistant to a political collapse, e.g. buying stunning equipment for fish slaughterhouses or wild-catch vessels

- working on preventing US collapse rather than working directly on a cause (or a win-win, like working on making ballot initiatives legal in states where they aren’t already)

- putting a small percent of the movement’s money into insurance, e.g. shorting US currency (?), some sort of futures contract, or whatever - or just making sure we’re not storing more money inside the US (or in forms that are linked to the US system) when we don’t need to

References

- Eig J. King: The Life of Martin Luther King. Simon & Schuster UK; 2023. 688 p.

- Freeman JB. The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War. Reprint edition. Picador US; 2019. 480 p.

- Molly B, Ball M. Pelosi. Illustrated edition. Henry Holt; 2020. 368 p.

- Canen NJ, Kendall C, Trebbi F. Political Parties as Drivers of U.S. Polarization: 1927-2018 [Internet]. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. (Working Paper Series). Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w28296

- Hogan RE. Legislative voting and environmental policymaking in the American states. Env Polit. 2021 Jun 7;30(4):559–78.

- Garlick A. Interest groups, lobbying and polarization in the United States [Internet]. Meredith MN, editor. [Ann Arbor, United States]: University of Pennsylvania; 2016. Available from: http://proxy.library.adelaide.edu.au/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/interest-groups-lobbying-polarization-united/docview/1868839434/se-2

- Thomas PEJ. Across Enemy Lines: a Study of the All-Party Groups in the Parliaments of Canada, Ontario, Scotland and the United Kingdom [Internet]. White G, editor. [Ann Arbor, United States]: University of Toronto (Canada); 2016. Available from: http://proxy.library.adelaide.edu.au/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/across-enemy-lines-study-all-party-groups/docview/2026754364/se-2

- Hosli MO, Selleslaghs J, editors. The Changing Global Order: Challenges and Prospects: 17. 1st ed. Springer; 2019. 483 p.

- Westwood SJ, Grimmer J, Tyler M, Nall C. Current research overstates American support for political violence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 Mar 22;119(12):e2116870119.

- Kalmoe NP, Mason L. A holistic view of conditional American support for political violence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 Aug 9;119(32):e2207237119.

- Jacobs, Milkis. What Happened to the Vital Center?: Presidentialism, Populist Revolt, and the Fracturing of America. Oxford University Press USA; 2022. 360 p.

- Jones SV. Law enforcement and white power: An FBI report unraveled. Thurgood Marshall Law Rev. 2015;41:103.

- Said W. Law enforcement in the American security state. 2019 Dec 1; Available from: https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/wlr2019§ion=32

Notes

-

Some policies might remain before and after the collapse of a political system. It’s hard to say. To make an analogy from historical events, say: you win some corporate commitment X immediately before the French Revolution. Then everything changes, and you end up with a totally transformed political system that affects all areas of life, especially contentious stuff like agricultural production. Or you win some corporate commitment Y in Weimar Germany right before the Nazi Party comes to power. Then everything changes, and you end up with one dictator who may or may not look kindly upon animal welfare and has the power to tell corporations and farmers exactly what to do.

-

A “party whip” is the senior official of a party within a legislature who is tasked with the job of making sure (as much as they can) that all of the representatives within that party, when voting on bills, cast their votes along the party line. Party whips are strong in the United Kingdom and Australia, where it is unusual to see Members of Parliament voting against their party on bills. Party whips are weaker in the United States, and it is more common to see Congressional representatives vote against their party on bills. That said, section 3.2 in this article might provide reason to believe that party whips are having more success in the United States lately. For academic papers on this topic, see Canen et al (4), Hogan (5), Garlick (6), and Thomas (7). This article section from Wikipedia also discusses the relative strength of whips in the United States Congress, an explanation that is supported by the academic literature: “While members of Congress often vote along party lines, the influence of the whip is weaker than in the UK system; American politicians have considerably more freedom to diverge from the party line and vote according to their conscience or their constituents’ preferences. One reason is that a considerable amount of money is raised by individual candidates. Furthermore, nobody, including members of Congress, can be expelled from a political party, which is formed simply by open registration. Because preselection of candidates for office is generally done through a primary election open to a wide number of voters, candidates who support their constituents’ positions rather than those of their party leaders cannot easily be rejected by their party, due to a democratic mandate.”

-

I feel similarly frightened by legislators’ use of the private individual enforcement mechanism (as in the Texas Heartbeat Act, among others) to prevent particular Acts from being reviewed in court; and by present willingness to turn to impeachment as a routine political tactic. I haven’t thought very hard about these trends and their implications - rather, even for a cynic like myself, it is just that these tendencies do not sit well with me.

-

The authors give a detailed explanation of this gatekeeping role: “Strong parties stand in the way of unbridled ambition by collectively investing an array of independently empowered individuals and the factions they lead with resources. They arbitrate fractious conflict among ambitious actors by channeling their diverse preferences through rules. […] Perhaps most important, strong but non-centralized party organizations can constrain presidential ambition. […] throughout American history executive aggrandizement has been moderated when members of the president’s own party have held him accountable. […] Strong party organizations thus temper populist unrest by creating an alternative set of incentives for party leaders, potential nominees, and the average citizen. […] Ambitious partisans are coaxed into supporting the institutional vitality of their organization, because no single individual or narrow faction can capture the party label, impose a personal style on its message, or dole out its largesse. The greatest threat to this collective responsibility is a charismatic president who might sacrifice party principle for personal preference - to a cult of personality.”