Soccer, the offside rule, and generational amnesia

Generational amnesia

In environmental science, there is a concept called “generational amnesia”. This refers to the idea that “each generation’s perception of what is “normal” in nature is shaped by their own experience rather than an objective standard” (Kahn 1999 cited in Craps 2024).

Generational amnesia is closely related to the concept of the “shifting baseline syndrome”. In a time and place where the environment is slowly but surely being degraded over time, a particular generation of people will grow up experiencing a particular state of the environment as normal. The next generation will grow up experiencing a slightly more degraded state of the environment as normal. From generation to generation, the baseline of what is considered “normal” shifts. As a whole, over the generations, human knowledge about the state of the environment is lost.

This concept has been powerfully applied in environmental politics and policy. In the marine ecology laboratory at the University of Adelaide where I studied for my PhD, work being conducted by others was applying the concept of “generational amnesia” to the extent of oyster reefs along the coast of South Australia. Heidi Alleway sifted through historical documents and demonstrated that South Australia had abundant and ecologically significant oyster reefs throughout the state’s coastline but that these reefs — and human knowledge about them — had been lost over the generations (Alleway and Connell 2015). This historical precedent provided powerful motivation for South Australia’s recent oyster reef restoration projects at Ardrossan and Glenelg.

The offside rule in soccer

So much for the environment. Let’s talk about sport.

In soccer, there is a rule known as the “offside rule”. The offside rule is defined in the Laws of the Game as Law 11. It actually takes four pages of text to fully define the offside rule.

In essence, it is an offence for a player to have any part of their head, body or feet past the final defender and to interfere with play, interfere with an opponent, or gain an advantage. These terms are all defined in legislative detail, with clauses and sub-clauses, in Law 11.

Like the United Nations, the offside rule is complicated for many professionals and hopelessly baffling for many outside observers. The offside rule is most frequently invoked when a striker has part of their body past the final defender when the striker’s teammate passes the striker the ball. It’s not an offence to be in an offside position — it’s perfectly acceptable to begin onside, have a teammate pass the ball into an offside position, and then run onto the ball — but it’s an offence to be in an offside position when the ball is passed and then take possession of the ball.

There are also fun corner cases. For example, a player is not normally considered offside if both the player and the ball are behind the final defender. However, if the goalkeeper blocks the ball from going into the goal and a striker in an offside position then scores a goal, that goal can be struck off due to the offside rule. This arcane exception has surprised even many professional players when it is invoked by a referee to cancel an otherwise legal goal.

Like the United Nations, the offside rule is nevertheless important. The offside rule basically prevents having a single striker always hanging out at the opponents’ goal — rather than simply hoofing the ball from one end of the pitch to another, strikers must work together and pass the ball to create goals.

In day-to-day games, ruling a play as offside (illegal) or onside (legal) is often up to the judgment of referees and assistant referees and, therefore, controversial for players and spectators. This was nailed by the Monty Python sketch “International Philosophy”, where teams of famous philosophers from Germany and Greece fought it out for the title. The commentator speaks:

Socrates heads it in! Socrates has scored! The Greeks are going mad, the Greeks are going mad. Socrates scores, got a beautiful cross from Archimedes. The Germans are disputing it. Hegel is arguing that the reality is merely an a priori adjunct of non-naturalistic ethics, Kant via the categorical imperative is holding that ontologically it exists only in the imagination, and Marx is claiming it was offside.

Changes in the offside rule over time

The only way that an offside rule can be constructed is to draw an imaginary and arbitrarily line… somewhere. This leads to many very close calls — many impressive goals have been ruled off due to the tip of an elbow or the tip of a toe being one inch past the final defender.

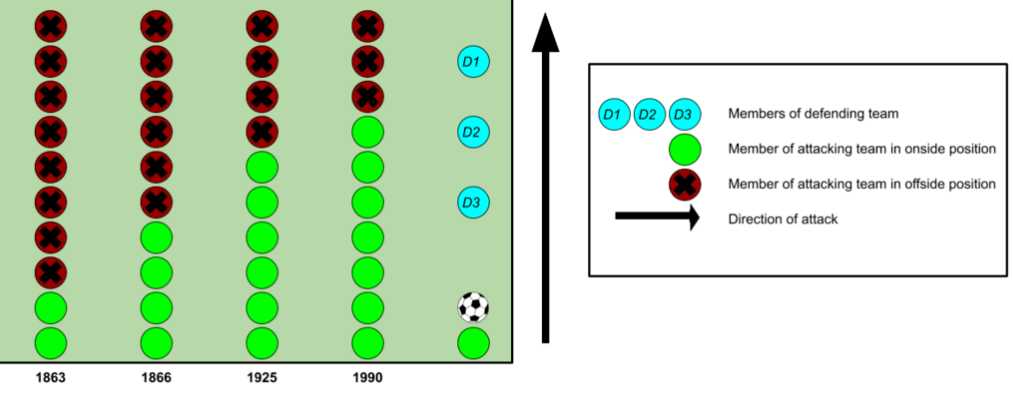

The offside rule has not always been defined in the way that it currently is. In fact, the line separating onside from offside has gradually crept forward over the past century or so. This illustration from Wikipedia depicts the changes over time (source):

In the 1800s, a player was offside if they were in line with the third-last defender! Over the generations, the line was gradually moved forward, until we end up with the modern offside rule where a player cannot have any part of their body beyond the final defender. Many soccer players and fans today are unaware of this history.

In fact, at the time of writing (April 2025), FIFA is trialling a revised version of the offside rule. This new rule essentially moves the offside boundary even further forward. This proposal is known as the “daylight” rule, as a striker is only offside if they are so far beyond the final defender that there is “daylight” (a gap) between the final defender and the striker.

The most interesting part about this new rule is how it is discussed in the media. There are frequent statements like “This rule will mean that players are not ruled offside due to a toe-nail.”

But, of course, that’s wrong! Players are not ruled offside due to a toe-nail because of the position of the offside line — rather, this is an inevitable consequence of the fact that there is a line separating onside from offside. It doesn’t matter where that line is. As long as there is such a line — whether it was in line with the third-last defender as in the 1800s, or the second-last defender of the 1900s, the final defender of the modern game, or beyond the final defender as in the “daylight” proposal — then it will be possible for a toe-nail to be the offending part of the body. The only difference is where the boundary is placed, and any boundary will inevitably lead to very close and disputed calls.

Suppose that the “daylight” rule is adopted as part of the Laws of the Game. Then, of course, as the next generation of soccer players and fans grow up, they will come to know this “daylight” rule as the natural boundary for offside. There will be close calls, where a player’s elbow or toe-nail was just slightly offside. Then, perhaps, there will be new proposals to move the offside line forward still, so that players are not ruled offside due to a toe-nail…!

Should there be an offside rule?

Ultimately, we play soccer because it’s fun to play, and we watch soccer because it’s fun to watch. All sports, including soccer, have completely arbitrary rules. It’s not just the offside rule that is arbitrary and complicated — the rules governing tackling other players, touching the ball with one’s hands, and throw-ins are equally arcane.

The point is to have a sport that is fun to play and fun to watch. Especially with the truly stupid amounts of money involved in the men’s game, it’s easy to forget that this is an arbitrary game. Professional soccer players are only a tiny minority of all soccer players around the world. In statistical terms, almost every soccer player is either a casual player in a community-level team or, perhaps more common, part of informal, pick-up games played in backyards, carparks, or council estates.

Abolishing the offside rule entirely would probably lead to some frustration as teams revise their strategies. But this is true for any rule — today, strikers spend a large amount of effort figuring out how to run at the exact right time to avoid being ruled offside. The inevitable close calls associated with the offside rule also lead to frustration, whether or not the referees even make the correct calls.

In smaller soccer matches, such as five-a-side soccer and indoor soccer, there is usually no offside rule. In cerebral palsy soccer, such as the IFCPF Women’s World Cup — where Australia’s ParaMatildas took home the gold in late 2024 — there is no offside rule. Other sports have different solutions; in rugby union, the problem is solved by prohibiting any forward pass.

The question is what sort of game we, as soccer players and fans, want to play. Do we want a game that requires more teamwork and passing, even if this means that some goals are struck off due to a marginal offside call and that new players have to take the time to learn this arcane set of restrictions? Or do we want a game where strikers have more freedom to make ambitious runs, even if this means that there is less teamwork and finesse? Perhaps there is a more creative middle way, like the training drills where a specific number of different players must touch the ball before a team can score a goal.

Any of these solutions are possible. They would all lead to slightly different versions of soccer, as has every change to soccer’s rules (and every variant of the game) over the history of the game. The question is what type of game we want to play and to watch. However, as history shows, pretending that simply shifting the offside line forward would effectively solve all controversial offside calls is misguided.