Tattoos that you need to earn

On the podcast Tides of History by Patrick Wyman, archaeologist Aaron Deter-Wolf reports this very interesting piece of information about historical tattooing practices (source):

So if we look, again, at this global sample of groups and cultures who tattooed historically, with the exception of those who were doing it as punishment, we see broadly that they are marks that are aspired to within the culture, and that not everybody is eligible to receive. […] And because of how these marks are used then within the society, because they confer elevated status, because they show someone who has having a, uh, a special relationship with the universe or ancestral spirits. These are things that a lot of people may have wanted, but just couldn’t go out and get. […] [W]here an individual had put tattoos on himself that he had not earned on the field of battle, and his community came together and actually flayed those off of him then, it was considered that much of a big deal that he had done this to try to impress people, but he actually hadn’t accomplished what was required of him. And so they were forcibly removed. That’s so fascinating. There’s so many questions I have about that that I want to follow up on. I’m never going to get to all of them.

I agree with Dr Deter-Wolf—this idea is so interesting! There are some specific tattoos that you can’t simply get because you want them or like them. Instead, you have to earn them.

I have noticed that these achievement- or status-specific tattoos still exist, in a way. To be clear, most industrialised or Western societies won’t actually flay your skin off for getting the wrong tattoo.

However, there are still specific tattoo designs that would feel wrong to get, and that would probably earn you social disapproval, unless you’ve earned them. Three examples are military tattoos, the Olympic rings tattoo, and pilgrimage tattoos.

Military tattoos

The book Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History contains this passage about the 1940s (Govenar 2000):

Chutes and boots were popular tattoos around those paratroopers, a lot of patriotic designs. I’ll tell you a guy had a hard-time if he had those chutes and boots put on before he took his first jump. That’s right. The rest of them guys worked him over if he got that tattoo too soon. The tattoo was a mark of accomplishment, and if you hadn’t accomplished anything, you didn’t deserve the tattoo.

Olympic rings

Many Olympic athletes get the classic Olympic rings as a tattoo. This is a common sight in professional soccer matches! The following photo shows the tattoo on the calf of handball player Larissa Araújo (Wikipedia):

Pilgrimage tattoos

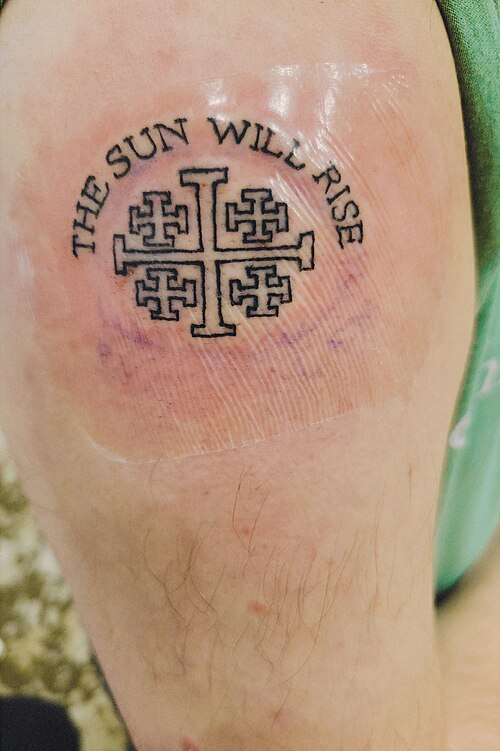

In some religious traditions, people may receive a tattoo to mark a pilgrimage. Christian pilgrims have received tattoos as early as the 8th century. In Jerusalem, there is a shop called Razzouk Tattoo that has been tattooing for around 700 years (Wikipedia). Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem often receive the Jerusalem cross tattoo (Wikimedia):

Against all expectation, this gets even cooler. Below are two historical portraits. The left portrait shows a nobleman, identified as Heinrich Wilhelm Ludolf (of Denmark). The right portrait shows Duke Siegfried von Kollonitz (affiliated with the Habsburgs), attributed to Frans von Stampart. (These portraits are discussed by Mordechay Lewy in a chapter on pilgrimage tattoos in the book Stigma, link. Lewy also discusses the admirable detective work that was required to find and identify these portraits!)

These two portraits show, on the wrists of each subjects, a pilgrimage tattoo! These particular tattoos contain the year of the pilgrimage (including the year is a common practice in pilgrimage tattoos). The portrait on the left shows the pilgrimage as having occurred in 1699, and the portrait on the right in 1700.

I find this amazing for a couple of reasons. First, you don’t often hear about European noblemen with tattoos, but here we have this practice recorded in portrait paintings. The aforementioned book chapter even reports that King Edward VII had a pilgrimage tattoo. Second, this is visual evidence of a practice that has existed for hundreds of years—it’s one thing to read that pilgrims have been receiving tattoos in Jerusalem for hundreds of years, but it’s astonishing to actually compare pictures of tattoos (e.g. those portraits vs the photo above) that are separated by a span of 300 years but united by a common tattoo tradition.

I also think these two guys look pretty badass with their tatts. Is there a Mrs Ludolf? ;)

Update 2025-06-02

Shoham (2015) writes about tattoo cultures among imprisoned people from the former Soviet Union, focusing on people from the former Soviet Union living in Israeli prisons:

[…] [A] criminal may not, under any circumstances, have a tattoo that was not approved and socially validated by his peers, and without the symbols actually matching the criminal’s nature. A criminal who “steals” a tattoo is actually taking a rank that he does not deserve. He will pay for such a deed by a painful removal of the tattoo and by ostracism, rejection, and alienation from the community. The more severe this theft act is, i.e., the more respect associated with the stolen tattoo is, the harsher the punishment will be. Even today, Israeli prisoners may be punished for identity theft with severe violence.