Challenging anxiety with the bell curve of mundane experiences

One of the many traits I’ve inherited from my beautiful parents is a terrible anxiety disorder. For me, navigating the landscape of anxiety requires constant work.

Over time, I have made a lot of progress, and this illness is now far more manageable than it was during my adolescence and early adulthood.

One of the most valuable tools that I’ve encountered is a book: The Cognitive Behavioral Workbook for Anxiety by William J. Knaus (link). The profoundly positive impact that this book — used in conjunction with long-term therapy, medication, and lifestyle adjustments — has had on my life cannot be overstated.

One of the gems of wisdom contained in this book is as follows. When you notice yourself magnifying negative pieces of information: “magnify every bit of information that suggests the opposite conclusion. Then ask yourself, What lies in between these magnified extremes?”

I find this really powerful because this doesn’t directly challenge the anxious thoughts — but more importantly, this isn’t simply positive thinking. Rather, the process is:

- Think about the worst case scenario, and collect the evidence supporting that negative extreme.

- Think about the best case scenario, and collect the evidence supporting that positive extreme.

- Ask yourself what lies between those two extremes.

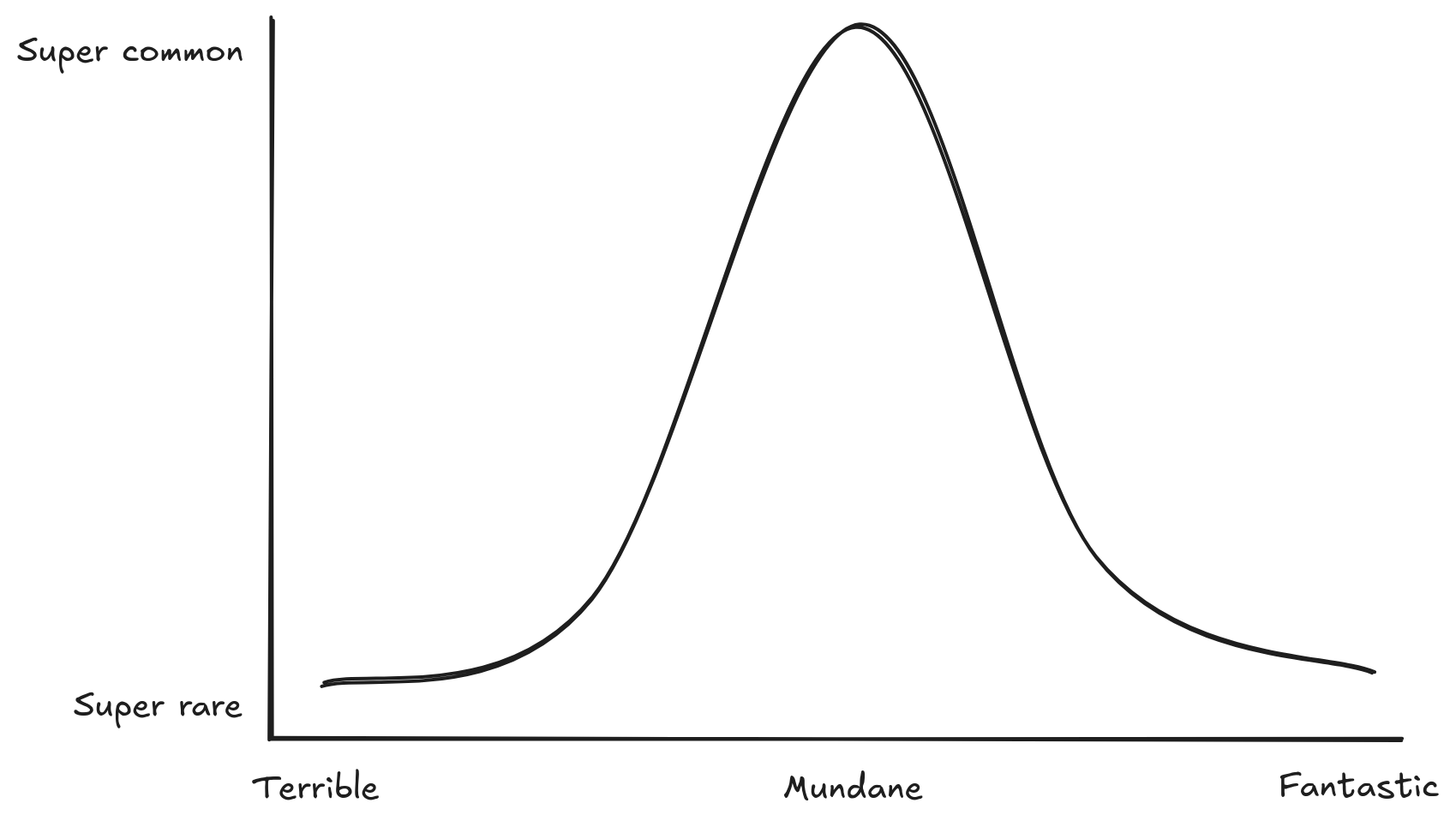

In my experience, this method works. And it works for one reason: life is ordinary. It is very rare that you experience a catastrophe — I might face a genuine catastrophe once every few years. But it’s also very rare that you experience unbelievably good luck — I might experience such a positive outcome once every few years. In the mean time, life is just mundane and even a bit boring.

Most life experiences aren’t fantastic and aren’t terrible; they’re the boring meat that makes up 95% of life. Over time, when I have noticed myself catastrophising and applied the above cognitive tool, I have noticed exactly that — almost everything turns out… unexciting. The friend doesn’t descend into red-hot hatred for you, and the friend doesn’t fall over with praise for you — the friend is busy and enjoys your company when they can. The family finances aren’t so bad that you’re going to lose you’re house, and they’re not so good that you can afford a vacation to Europe — you have a little bit of money that you can spend wisely.

And mundane is great! For that wonderfully mundane 95% of life, your life is what you make of it.